Professor Andersen, everyone talks about the “special” Danish corporate culture. Why do Danes seem so satisfied with their employers?

Andersen: On the one hand, because we Danes want to feel comfortable everywhere – not only in our private lives, but also at work. We are often described as a people who like things to be “hygge”, cosy. At the same time, this does not mean that we are not hardworking - quite the opposite. Many Danes have a very strong work ethic.

Where does that come from?

Employees are given a great deal of freedom within companies - and at the same time they carry a great deal of responsibility. Everyone is encouraged to make decisions themselves, and everyone expects to be heard by management if they have ideas, want to renegotiate something or seek personal feedback. This culture of listening and communication has been deeply embedded in Danish corporate culture for more than a hundred years. It also shapes the rules and structures of the labour market.

Does this openness promote innovation?

Yes – especially at a grassroots level. Someone on the production floor might say: “This is inefficient, we can do it better.” Such input is not lost. Flat hierarchies in Denmark are not a marketing slogan: shared lunch tables with the CEO, an awareness of the company as a whole rather than just one’s own department - all of this lowers barriers and encourages innovation.

Danish companies are strongly export-oriented and therefore have to react quickly to changes in the market. How does this affect employee turnover?

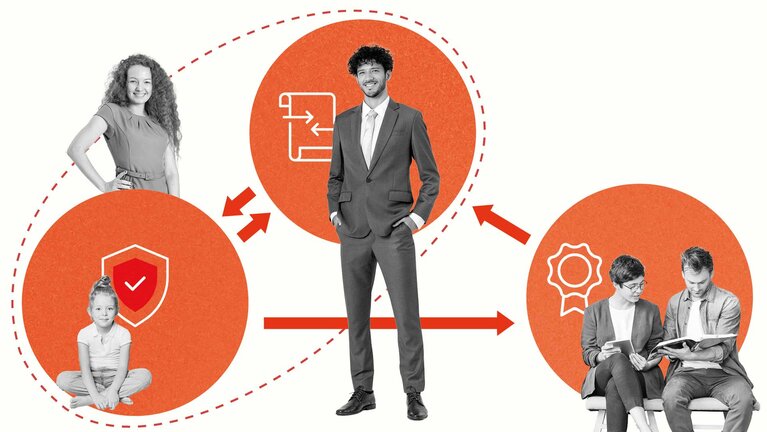

Denmark has found a solution in the flexicurity model. It is based on three pillars: flexible labour market policies, a comprehensive social security system and a strong commitment to lifelong learning. This integrated strategy allows companies to adapt their workforce to market dynamics without jeopardising employees’ stability or development opportunities.

How does this dynamic work without employees fearing for their jobs?

The fear of unemployment is mitigated by the fact that continuous training is a cornerstone of the flexicurity model. Denmark prepares its workforce early for the uncertainties of a rapidly changing economic landscape. This commitment to continuous skills development ensures the adaptability and competitiveness of Danish workers. That is why Denmark has a highly resilient, dynamic and inclusive labour market.

It sounds positive - but doesn’t this flexibility also mean more insecurity?

The fact is that job changes happen frequently, yes. But re-employment usually works very quickly, because qualification and placement systems function well. This reduces fear rather than increasing it.

How long has this Danish balance between freedom and security existed?

Since the turn of the 20th century. After severe conflicts between employers and trade unions, both sides agreed at that time on a clear division of roles: management runs the company, trade unions negotiate wages and conditions - on the basis of voluntary agreements. This remains the DNA of the system to this day.

What does this culture look like in everyday company life?

There are many examples. People address each other by first name, for instance. If someone suddenly uses your last name, you know things are getting serious. This closeness speeds up decision-making - problems are addressed before they escalate. Work-life balance is normal, not a bonus. Flexible working hours, understanding for parents, including those in management positions - all of this is standard practice. It supports women’s careers and is taken for granted in small and large companies alike.

Where are the limits of the model?

It works well when the economy is strong. In prolonged periods of crisis, however, it can come under pressure. In the 1970s and 1980s, Denmark went through a deep crisis. Unemployment was high and linked to many political mistakes. At that time, the model was seriously questioned. But reforms helped to stabilise it.

Does this type of corporate culture contribute to international success?

It helps – but it is not the only reason. What is also crucial is that Denmark has always been export-oriented and internationally connected. Trade barriers or protectionist tendencies therefore hit us particularly hard - which we offset through market diversification. Companies expand into new business areas, markets and customer segments because they can and because they must. This helps to safeguard their future.

What is special about the Danish approach for you personally?

Trust – between employees, companies, trade unions and the state. Without trust, our system would not work. Flexicurity is therefore not just policy, but culture.